The State of Competition Policy in Canada: Towards an Agenda for Reform in a Digital Era

Vass Bednar & Robin Shaban

April 21, 2021

About the Authors

Executive Director, Master of Public Policy in the Digital Society Program at McMaster University

Vass Bednar is an interdisciplinary wonk focussed on ensuring that we have the regulatory structures we need to embrace the future of work and new ways of living. A graduate of McMaster University’s Arts & Science Program, Vass holds her Master of Public Policy (MPP) from the University of Toronto and successfully completed Action Canada and Civic Action DiverseCity Fellowships. She has also held leadership roles at Delphia, Airbnb, Queen’s Park, the City of Toronto, and University of Toronto. Passionate about public dialogue, she was also the co-host of “Detangled,” a weekly pop-culture and public policy radio show and podcast that ran from 2016-2018. She currently writes a newsletter about Canadian startups and public policy called “regs to riches” and was recently recognized as a Public Policy Forum Fellow.

Principal at Vivic Research

Robin Shaban is co-founder and senior economist of Vivic Research. She is also a PhD candidate at Carleton’s School of Public Policy and Administration, studying competition policy in Canada and around the globe. This year she was also a winner of the Globe and Mail’s Report on Business 2021 Changemakers award. Since 2017 she has worked as a consultant serving several think tanks and advocacy organizations such as the Ontario Living Wage Network, the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, the office of the EI Commissioner for Workers, the Broadbent Institute, and others. Prior to that, she was the Andrew Jackson fellow at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and an officer at Canada’s Competition Bureau. Robin holds a MA in economics from Queen’s University.

About the Series

In this essay series, Platform Governance, McGill’s Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy explores the policy, legal and ethical issues of platform governance faced on a global scale.

Digital platforms such as Facebook, Amazon and Google increasingly midiate core functions of our society, economy and our politics. Platform companies increasingly define and govern our public values, speech, social interactions, our digital economy, as well as filter access to the internet and essential services more broadly. As global technology infrastructure, they often do so outside of the bounds of national laws, regulations and norms. As such, understanding how they function and how they can be governed has become a core policy challenge of the 21st century. The Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy seeks to understand and help develop public policy governing digital platforms.

Abstract

This paper reviews the current state of competition policy in Canada. It begins by contextualizing the purpose and goal(s) of competition policy against recent antitrust events in response to the power of large, dominant tech firms like Facebook, Google, Apple and Amazon. It then surveys a brief history of antitrust actions and subsequently considers the different schools of thought within competition policy discourse that have come to characterize competition policy before focusing on the features that distinguish competition policy approaches in Canada from those in the US or EU. It concludes by briefly considering opportunities for Canada’s competition policy to be at the forefront of the digital economy.

“The primary objective of competition policy is to enhance consumer welfare by promoting competition and controlling practices that could restrict it. More competitive markets lead to lower prices for consumers, more entry and new investment, enhanced product variety and quality, and more innovation.” -- OECD, 2012

“The capitalist economic system, whether you value it or not, relies on competition. At its best, competition keeps companies honest, narrows costs, expands the job base, sows innovation, distributes the fruits of productivity widely, and gives every member of society a chance to use their talents to earn a living. Competition protects economies, affords possibility, and allows democracy to flourish, as no one firm becomes big enough to control the corridors of power. That’s the theory, at least, and historical evidence bears it out. America’s best moments of shared prosperity line up favorably with eras of robust competition, when government-appointed guardians attacked efforts to corner markets.”[1]

I. Introduction

In Canada, the Competition Bureau is an independent law enforcement agency headed by the Commissioner of Competition, which is responsible for fostering a competitive and innovative Canadian marketplace. When a country or other jurisdiction has adequate laws, policies and funding for enforcement, Competition agencies like the bureau can ensure that there is a healthy amount of competition among businesses that promotes consumer choice.

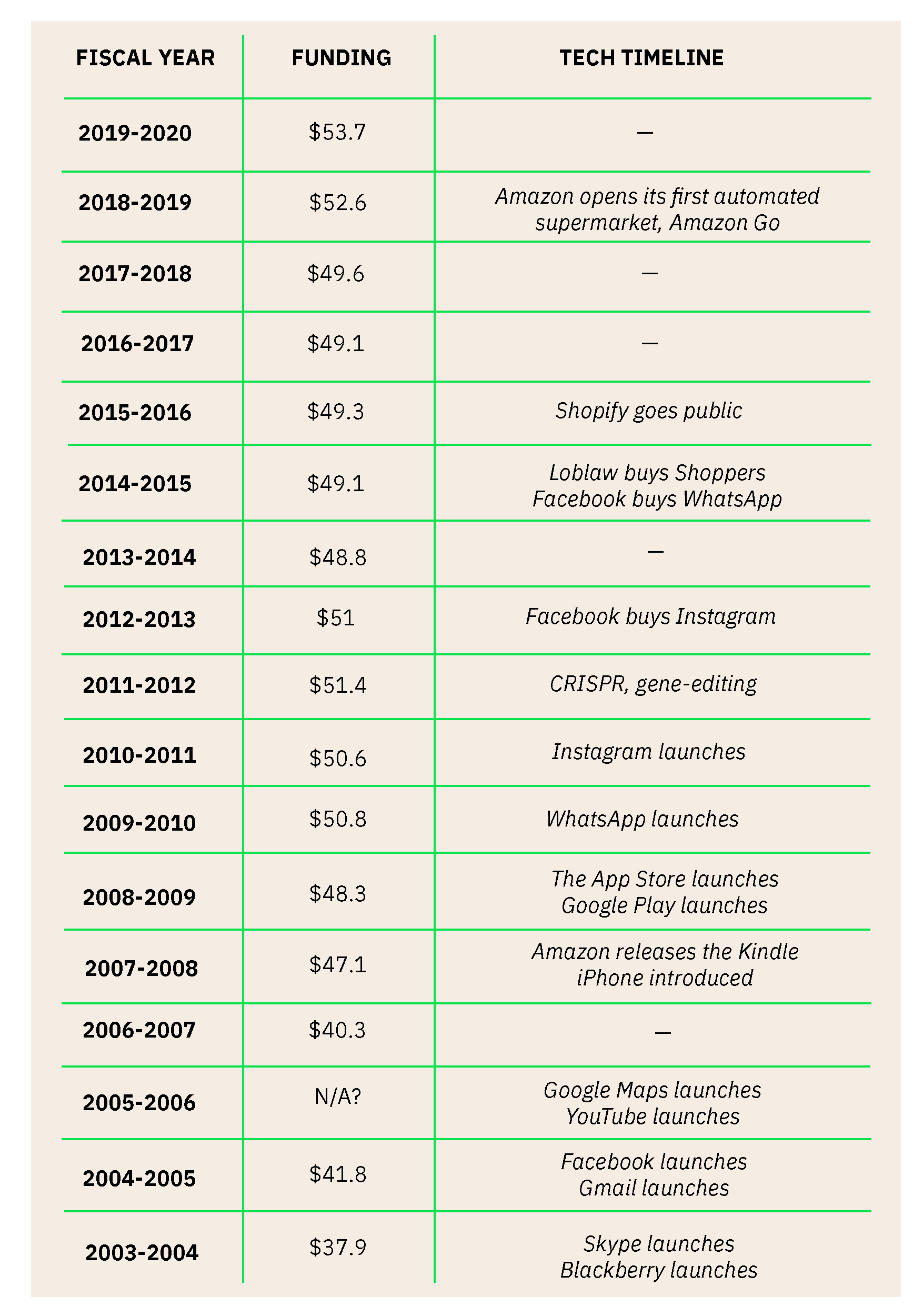

Canada’s Competition Act was not designed to protect competition in the digital world. The unique characteristics of the relatively novel digital commerce sector and the digital economy more broadly make it substantially easier for firms to achieve dominance and maintain that dominance. The Competition Act was enacted in 1986, but the understandings of competition and the economy were based on theories and realities going as far back as the late 1960s. In the decades since the Act was first implemented, technology has changed dramatically: the original iPod launched in 2001, Skype was founded in 2003, Facebook was founded in 2004, YouTube first launched in 2005, Canada’s most valuable company Shopify was founded in 2006 and the first iPhone as well as the original Amazon Kindle were released in 2007. The architects of our current Competition Act could never have conceived of the challenges of protecting competition in the digital era, particularly the role of data in creating and reinforcing dominance.

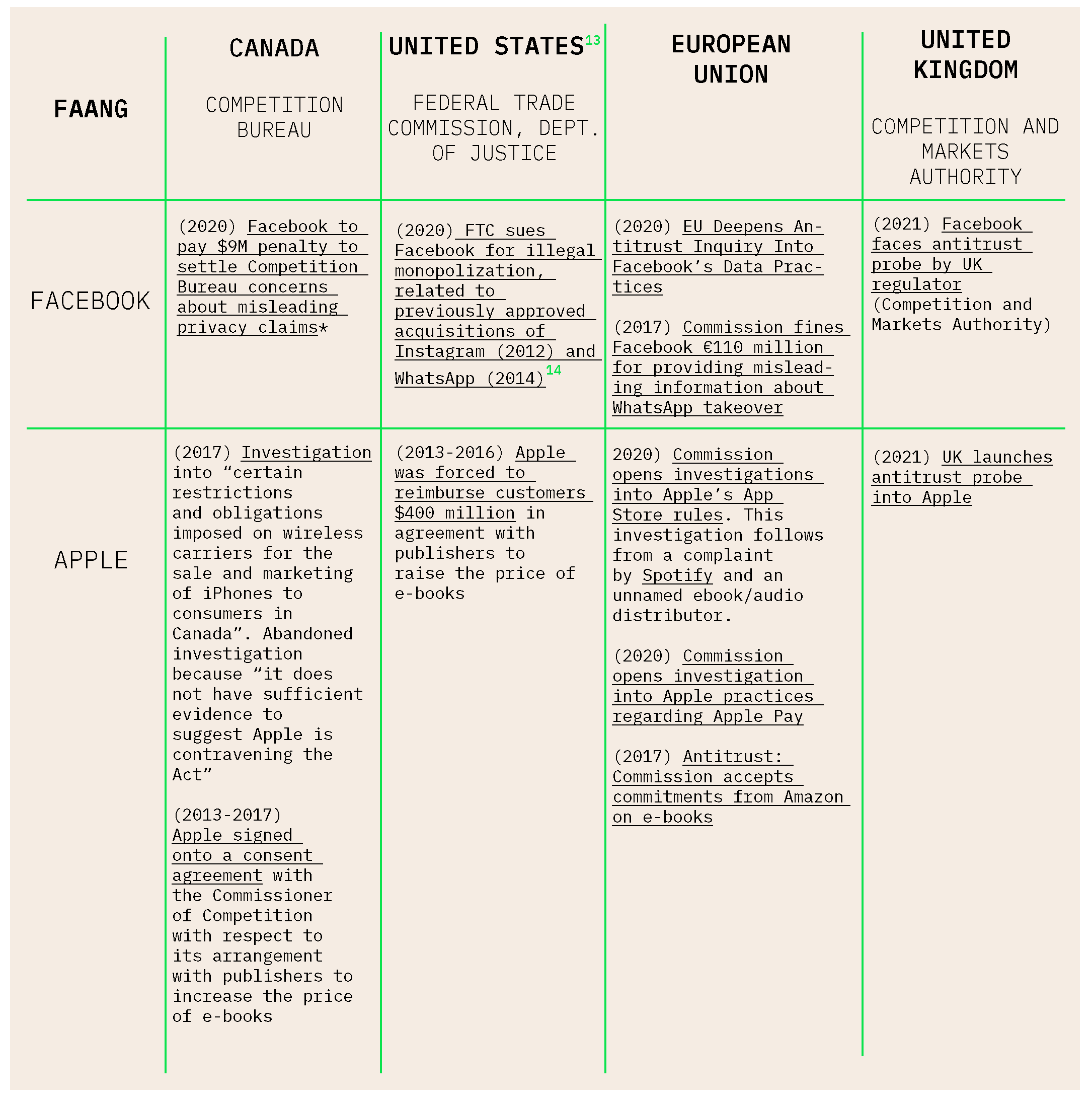

In both Canada and abroad, there are heightened concerns regarding the growing dominance and outsize influence of large digital companies on our lives and democracies. Lawmakers in the US and competition authorities in both the US and EU are seeking to prove that technology companies like Amazon, Facebook and Google monopolize digital markets and abuse their power (Appendix B). Meanwhile, some critics point out that the real social problems caused by these technologies and their use of data to gain power in our society, like the amplification of hate and misinformation and the subversion of democracy aren’t related to competition. Thus, these issues are unlikely to be resolved through antitrust efforts as they are more related to the business models of digital firms and are amplified by their size, not caused by it.

Global Context

Competition authorities in the US and EU are beginning to take decisive action against the “digital giants”, despite the complexities of enforcing competition law in this sector.

The European Commission (EC) and the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have initiated serious actions against Facebook. The FTC filed an abuse of dominance case with the aim of having Facebook divest itself of Instagram and WhatsApp, which Facebook acquired in 2012 and 2014, respectively. Meanwhile, sources including the Wall Street Journal suggest that the European Commission is currently investigating whether “Facebook leveraged its access to its users’ data to stifle competition.”

Amazon

In 2020, the European Commission launched investigations into Amazon’s use of third-party seller data and its logistics and delivery service to enhance its own retail business. In 2015, the Commission also struck an agreement with Amazon requiring it to remove its “most-favoured-nation” clauses from ebook distribution agreements, which led to higher prices. Canadian and US authorities have never undertaken public investigations into these matters.

Apple

Canadian, American and European authorities all brought cases against Apple for its agreement with book publishers to fix the price of ebooks. In addition to this, the European Commission recently opened investigations into Apple’s App Store, Apple Pay and Apple Music. Canada began investigating Apple, but closed the investigation in 2017.

Alphabet/Google

Since 2011, the Competition Bureau has launched five modest investigations into the largest Big Tech giants oftentimes referred to as “FAANG”: Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google. During this period, authorities in the US and the EU have launched nearly double and triple that amount, respectively.

The European Commission has also been proactive against Google. In 2017 and 2019, it fined the company 2.42-billion and 1.49-billion euros, respectively, for abusing its dominant position with respect to its Google Shopping and AdSense services. Canadian and US authorities did not follow suit. In fact, in its 2013 investigation, the FTC found that there were no competition issues with Google’s use of Google Shopping, contrary to the EU finding five years later.

The European Commission also put restrictions on Google’s acquisition of Fitbit in an effort to control the tech giant’s use of health data to better target advertising. The investigation is still being reviewed by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and there is no sign that the Competition Bureau will review the deal.

Canadian Context

There are structural limitations in Canada’s legislation that hinder its ability to curb anti-competitive practices, putting Canada at a disadvantage compared to other developed countries. Further, the Competition Bureau has typically been a passive bystander or a second mover to these historic suits, though it has recently taken some initiative in the area.

The Bureau’s lack of aggressive action is particularly troubling given that Canada has its own large, sophisticated technology companies that dominate in the e-commerce, insurance, grocery and data domains, like Shopify (e-commerce), Manulife (insurance) and Loblaw (“George Weston Limited,” everyday essentials). Many of the competition issues related to data and the digital economy in the US and EU are mirrored in the Canadian context, but have been under-studied by scholars and officials alike.

These new issues – the ability to scale faster and achieve dominance, the use of data to manipulate price and potentially mimic products and undercut competitors, the outsized role of these firms as market gatekeepers, the ability to control our attention and influence our behaviour and new manifestations of monopsony (monopoly power held by purchasers rather than sellers) in labour markets – challenge existing legislation and warrant modernization.

The US and EU have distinct regulatory environments with a different standard of proof when it comes to establishing anti-competitive harm. They also have substantially more resources. These two realities empower both bodies to be bold in a digital competition context in ways that Canadian authorities can not be. Further, part of the EU’s proactiveness relative to that of the US and Canada may be due to the EU’s role as a net tech importer, lending it political license to antagonize American tech giants.

In this paper, we demonstrate that Canada’s competition policy is not up to the task of protecting competition in a digital economy. Last updated[2] over a decade ago, Canada’s system is unable to reliably address current issues in our economy such as algorithmic accountability, the growing dominance of digital firms, the role of data in creating competitive advantages; digital monopolies creating surveillance capitalism; or the increasing consolidation of media.

That said, competition policy is hardly anticipatory; it is inherently reactionary and evaluates mergers and markets after firms have grown or acted in a particular manner. The risks of extreme dominance by digital firms and the obvious harms on the horizon that their growing power can bring make it necessary for Canada to improve its competition policy environment now because it is likely that Canadians will have to take action in the future, given the ubiquity of large technology firms in our everyday lives.

The deficiencies of Canada’s competition policy in this area are largely due to outdated understandings of competition that have influenced both the design and enforcement of its competition laws. But Canada is not alone in this inability to modernize competition law for the digital era. Competition authorities around the world have not yet fully understood the global role of data and technology in the context of competition. This has led competition authorities to overlook business behaviour that undermines competition.

At the same time, public conversations about competition policy and associated antitrust activities can seem boring (at best) or inaccessible (at worst) to the average citizen. But these tools matter. Indeed, it hurts the competitiveness of the country to not focus on the importance of competition policy and advocate for its modernization, as it is an important driver of innovation and economic equity.

Canadians need to reimagine the nation’s competition policy so it meets the needs of their modern, digital times. To do this, Canada must reconsider the concept of competitive “harm” within competition policy so it can better identify and prevent business activities that hurt competition. When "consumers" are trading their data in exchange for a product or service, the traditional understandings of competitive harm, which is based on neoclassical economic theory that assumes a consumer exchanges money for a product or service, no longer hold true. Our traditional ideas of efficiency also become increasingly warped in a world with zero or low marginal costs and increasing monopsony power that grinds away at workers and increases worker precarity.

Competition policy is a highly relevant policy lever for the forces that are reshaping media, technology and democracy. Alongside other levers, like digital taxation and privacy legislation, competition policy is a significant tool to limit the growing dominance of data-driven companies and create new accountabilities for the associated harms to the economy and society. We must sharpen the tools in the policymaker’s tool chest to better regulate these firms and protect people from new and future online harms. This paper offers a brief list of areas of opportunity for policy makers to consider.

II. Canadian Competition Policy in a “Nutshell”

Competition policy is the suite of laws, regulations, law enforcement and processes designed to regulate competitive behaviour between businesses. In Canada, the competition authority is the Competition Bureau and it is headed by the Commissioner of Competition. The Bureau enforces Canada’s competition law, the Competition Act, last revised in 2009.

The specific goals of competition policy have varied across place and time. But the general idea that motivates competition policy is that promoting and regulating competition creates beneficial outcomes for the economy and society, including greater economic efficiency and innovation, more product variety for consumers and better prices, the ability for entrepreneurs to start businesses and bring new products to market and overall economic fairness.

The idea that the core goal of competition policy is efficiency was imported from the US in the 1960s. At that time economic and legal thinkers at the University of Chicago, often called the “Chicago School of economics” were reimagining competition policy. A leading thinker in the field, Robert H. Bork, wrote the seminal book The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy At War with Itself, which presented a revisionist history of American antitrust law. The crux of his argument was that antitrust law was not intended to promote an egalitarian economy, contrary to what legislators had articulated. Rather, the true, underlying purpose of antitrust was to promote efficiency.

Following that logic, Bork argued that antitrust laws should be less aggressive. Competition policy should only intervene in the most extreme cases since competition is a self-reinforcing system. In fact, market power can be good, because it leads to “dynamic efficiency” by incentivizing incumbents and gives firms the resources they need to create innovation (à la Schumpeter). By the 1980s this thinking became so pervasive in the US that senior decision makers in the US’s competition policy system were seeking to have Congress repeal the antitrust laws. The extreme view of competition and competition policy held by Chicago economists, described as “right-wing radical” by some, has been attributed to lax enforcement of competition laws and the digital giants we see today.

Canadian thinkers embraced this Chicago School perspective on competition policy and the Economic Council of Canada was instrumental in bringing these American ideas into the Canadian dialogue. The Interim Report on Competition Policy, published in 1969 by the Council, highlights clearly the prioritization of efficiency over equality and other non-efficiency considerations. The thinking outlined in the Report is that other forms of policy, like taxation, are better suited to redistributing resources and diffusing economic power. This understanding of the role of competition law has continued to inform thinking today.

There are three key classes of business conduct that competition policy is concerned with: mergers (mergers and acquisitions or “M&As”), abuses of dominance and collusive agreements (cartels, conspiracies, bid-rigging, etc.) that violate both civil and criminal laws. The Commissioner (the Competition Bureau) has the power to investigate mergers, agreements between competing businesses or certain business practices to assess whether they undermine competition in the market, as defined by the Competition Act. The Competition Bureau also enforces on issues related to misleading advertising and labelling. However, for the purposes of this paper, we are more concerned with the implications of monopolistic digital advertising platforms than we are misleading claims.

If the Commissioner finds that a merger, a competitor collaboration or a business practice of a dominant firm (or dominant group of firms) undermines competition in Canada they can choose to legally challenge that conduct. In cases where businesses have violated civil laws (harmful mergers, abuses of dominance and some collusive agreements), the Commissioner could file a case with the Competition Tribunal, a quasi-judicial body that hears exclusively competition cases. The tribunal is made up of both judges and non-judges (“lay members”). Alternatively, under the threat of legal action, the Commissioner may settle with the businesses by establishing a consent agreement. Under the agreement, the businesses are typically required to cease the problematic conduct or divest of its assets. Importantly, the Commissioner can apply the law to companies that operate in Canada, even if they are not headquartered here. The same is true for many other jurisdictions.

Competition policy in Canada is not a static suite of policies that are implemented by the government, like other forms of industrial policy. It is a dynamic system of laws, jurisprudence and enforcement decisions that are evolving and are shaped by the views and judgments of actors that participate in the system. As the leader of an independent law-enforcement agency, the Commissioner makes decisions about whether certain business conduct will be investigated and what cases to take to the Tribunal. Under the common law system, the decisions made by the Tribunal and courts lie with the federal appellate court, and the Supreme Court define and refine Canadian competition law. And the law itself, developed by parliamentarians, is informed by economic thinking on competition. Therefore, Canadian competition law and policy is shaped by the beliefs and understandings of actors that participate in the system, whether they are correct or not.

III. The Problems of Digital Dominance and its Consequences

“Digital dominance” describes digital companies that have achieved significant market scale to which there are little to no alternatives in markets. Competition policy is relevant to digital dominance as it creates the conditions for anti-competitive firm behaviour. A recent report described how digital markets operate and that their very structure may facilitate anti-competitive practices.

A 2020 report published by CompTia, the nonprofit association for the global technology industry cited Canada’a net tech employment at 1.72M workers, with 73,000-plus tech businesses across the country. Canada’s tech sector accounted for 4.7% of the overall Canadian economy in 2019, up slightly from 2018.

While our home-grown tech sector may account for about 5% of the country’s GDP, the digital giants (“FAANGs” – Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) have an outsize role in our everyday lives. In Canada, Facebook is by far the most used social media platform: 83% of Canadain adults have a Facebook account and 79% of daily social media users log into Facebook. These statistics do not capture the use of Instagram or WhatsApp, two other key social media platforms owned by Facebook. Nearly half of all Canadians report having an Amazon Prime Account (42%), and 78.1% of all people in Canada who use streaming services have a Netflix account. And last but not least, Google holds 92% of the market for search and 50% of online advertising.

What is more, the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the dominance of these firms. Amazon’s earnings have increased by 57% ($10.7B US) over 2020 as more people turn to online retail. Firms are also devoting more dollars to online advertising, leading to Google, Facebook and Amazon’s takeover of the US ad market. These three companies now receive a majority of US ad dollars (not just digital) creating an advertising “triopoly.” Much of the public discourse related to these digital platforms focuses on the potential threats they pose to markets, financial institutions and democratic processes.

There are unique characteristics of the digital economy and commerce that have led to the incredible dominance of the FAANG companies (and others), which in turn undermine competition in both Canada and abroad. In 2019, the European Commission published, “Competition policy for the digital era,” which analyzes the main characteristics of the digital economy, “extreme returns of scale of digital services, network externalities and the role of data – which have given rise to large incumbent digital players.”

Leading digital firms have the ability to scale to unprecedented size due to low or zero costs of expansion in their user base. These digital firms are not bound by the physical constraints of geography or anchored in brick-and-mortar establishments, making it easier for them to achieve massive scale quickly. They also function round-the-clock. In the past, the average Fortune 500 company would take 20 years to reach a billion-dollar valuation, but digital startups can now do it in four years.

With this scale, firms can collect detailed data on users and customers, which further reinforces their dominance. Detailed datasets allow firms to build increasingly sophisticated profiles of customers, sometimes across seemingly disparate sectors. These datasets, in turn, provide firms with massive competitive advantage. Firms can use this data to create products that replicate successful products of other companies, with potentially catastrophic consequences. For example, Amazon employees say that the company used data from third-party sellers to make its own products. Amazon can also advertise their own products first, because they are both a platform and a marketplace. The case of [Quidsi, the startup behind diapers.com] demonstrates Amazon’s ability to aggressively squelch competitors and sets a dangerous precedent for Amazon to extend this tactic to other products.

The massive scale of the leading digital firms and their roles as both platforms and marketplaces also positions them as gatekeepers to markets, further entrenching their dominant position.

The rising dominance of these digital firms presents serious problems to competition and the welfare of society in Canada and around the world. A 2018 article from “Promarket” surveys Solutions to the Threats of Digital Monopolies writes:[3]

“Some point to the mere size, power, and unregulated conduct of these digital monopolies. Others focus on the unprecedented scale and speed with which personal data is collected and used in the context of prediction algorithms, an omniscient, opaque machinery that threatens to erode the very foundation of privacy. Still others highlight the ability of digital monopolies to control much of our attention, which allows them to dictate which content we are exposed to and to influence our behavior. In this “economy of attention,” users’ eyeballs have become the main commodity traded.”

The swaths of data that leading digital firms can access due to their massive scale gives them dominance. From this dominant position, they can use this data to control pricing, undercut competitors and replicate the products of competitors. These risks are best outlined in Lina Khan’s 2017 article, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” Khan illustrates Amazon’s tactics as both a platform and a marketplace that can collect massive amounts of information on competitors, replicate their products, under-cut on price and then dominate the market, reframing decades of monopoly law.

These examples demonstrate the blatant consumer harm that dominant digital firms can inflict as a result of their scale and large datasets created by tracking consumers online. Shoshana Zuboff’s seminal description of “surveillance capitalism” has helped to capture the new economies of user data and exploitation that have come to characterize our digital lives.[4] Cory Doctorow’s “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism,” counters that Zuboff over-states the power that targeted advertising has the innate power to influence human behaviour and instead offers that she is ultimately describing a problem of monopoly.

In Canada, these trends are present on a smaller scale. For instance. Loblaw Companies Ltd.’s digital deepening across finance (PC Financial), health (Shopper’s Drug Mart) and the grocery spaces provides a novel case study of market power achieved through improved matching and reduced privacy as they refine their proprietary advertising platform, Loblaw Media, emulating a playbook refined by Facebook and Amazon. While this may limit competition, it can also harm consumers by constraining their ability to access everyday essentials at a cheaper price.

The rapid digitization of the world is also reshaping labour markets. For tech workers, rising concentration in the sector makes it easier for companies to collude (either explicitly or tacitly) to exert monopsony power to keep wages low. The FTC’s 2010 action against several tech companies, including Apple and Google and others, illustrates how tech firms can use non-poaching agreements to suppress tech worker’s wages.

Digital platforms are also increasingly taking on a new role as intermediary between independent contractors and flexible employment opportunities (e.g., ride-hailing drivers like Uber and food and grocery delivery like Instacart). In a competition context, the rise of these digital platforms has led to increased monopsony power – where purchasers can exert undue control over the prices of “sellers”, including workers (think the inverse of monopoly). For example, a 2018 study of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform and its monopsony power,, found that workers were paid 13% less than they deserved based on their productivity. And this problem is only going to get worse as digital platforms tied to labour markets—Uber, Foodora or TaskRabbit, just to name a few—become even more prominent and seek to incentivize those that they contract with to abandon their competitors in order to earn greater market share.

Lastly, as Promarket and others have pointed out, the dominance of digital firms is also dangerous for society and democracy. The largest digital companies have revolutionized how we share and receive information. Access to that information, as well as information about individuals that digital companies can amass and leverage, are a source of political power and control, amplifying extremist views that can lead to radicalization and even violence. The utter domination of these firms and their pervasiveness in our lives gives them the power to influence what we consume, where we work, how much we make from our labours, what media we view and even democracy itself. These firms have come to monopolize aspects of the economy and characterize our lives.

This is compounded by the fact that there is a great deal of asymmetry with online platforms and digital advertising whereby people pay nothing to access the social media platform’s network but advertisers pay a lot of money to target their ads online. For instance, it was recently found that Facebook lied about video metrics, potentially inflating the price that advertisers paid on the platform and advertisers had no way to verify this.

IV. Attempts to Address the Problem

Competition authorities outside of Canada have taken some early antitrust action against the largest technology firms. The outcome of these cases will be informative to Canadian policymakers, who have signalled that safeguarding competition in a digital world is a priority.

In the US, there are antitrust suits against Google that accuse it of using anti-competitive behaviour to maintain its search and search advertising monopolies and alleging that it uses monopolistic power to control pricing and engage in market collusion to rig auctions.The FTC has also sued Facebook in December 2020, accusing the social media giant of buying potential competitors to choke competition. The suit demands that Facebook unwind its acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram.

In Europe, there are active antitrust cases against Amazon’s use of big data, claiming that it used independent sellers’ data to benefit its own retail business. The EU also launched an investigation into Google’s proposed acquisition of Fitbit. The EU has been the most aggressive when it comes to penalizing the largest technology players, likely somewhat empowered by their status as a net tech importer. In June 2017, the Commission fined Google €2.42 billion for abusing its dominance as a search engine by giving an illegal advantage to Google's own comparison shopping service; and in July 2018, the Commission fined Google €4.34 billion for illegal practices regarding Android mobile devices to strengthen the dominance of Google's search engine.

In Canada, the current Commissioner of Competition has committed to doing more enforcement in this area through annual reports and various speeches. As the Commissioner has stated, “[I]t is clear that the Canadian economy is more digitally focused than ever before, and the growth of our digital and data-driven economy will likely only accelerate in the years ahead.” The Bureau has taken enforcement action in an online context with firms like Ticketmaster and FlightHub on false and misleading advertising. As follow through on this commitment, the Competition Bureau is currently investigating Amazon.ca for potentially harming Canadian businesses. As part of this investigation, the Bureau issued a call for businesses to report potentially anti-competitive conduct in the digital economy.

While this paper previously focussed on the trifecta of mergers, collaborations and abuse of dominance, Canada’s Competition Bureau has taken considerable action when it comes to misleading advertising. Misleading advertising is a competition issue because it undermines the ability of fair and effective operations of a market. This is notable in the context of reviewing competition policy for a digital age, as the Bureau is less critical of the monopolistic nature of big tech’s advertising platforms.

In an effort to remain relevant in a digital world, the Competition Bureau has also undertaken policy work in the area of the digital economy. The Competition Bureau’s most recent annual report focussed on Safeguarding Competition in a Digital World where the Bureau shared highlights of its “high impact and consumer focused enforcement” and outlined how it works to promote pro-competitive policies and regulations through forward-thinking advocacy, international collaboration and strengthening domestic relationships. For instance, the Bureau has called on businesses to report anti-competitive conduct in the digital economy, and has also cracked down on social media influencer marketing.

In 2019, the Commissioner appointed Canada’s first Chief Digital Enforcement Officer (CDEO). That same year the Bureau also held a one-day Data Forum in 2019 to discuss competition policy in the digital era and committed to working with the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) to look at: the impact of digital transformation on competition; emerging issues for competition in data accumulation, transparency and control; and the effectiveness of our competition policy tools and frameworks, and our investigative and judicial processes. The Competition Bureau has also recently expanded its market intelligence efforts re: anti-competitive acquisitions in the “kill zone.”

As part of its recent commitments to tackle competition issues related to tech, the Bureau has also acknowledged the international scope of the problem. A speech by a Deputy Commissioner at the Bureau delivered in late 2020 on Consumer Protection in Unpredictable Times acknowledged that borderless challenges call for borderless solutions. The Commissioner also acknowledged that “with such a deep reliance on these technologies, we can see a heightened risk to consumers.”

Parliamentarians are also aware of the issue and have signalled a need to address it. One of the recommendations in the 2018 Canadian House of Commons report “Democracy Under Threat: Risks and Solutions in the Era of Disinformation and Data Monopoly” is to “study the potential economic harms caused by data-opolies and determine whether the Competition Act should be modernized.” In a year-end interview with the Globe and Mail, then-Minister Navdeep Bains was asked about updating the Bureau’s toolkit for the digital economy. In his response, he acknowledged that the federal government will be “looking at the Competition Act.” However, after a Cabinet shuffle in January 2021, the Supplementary Mandate Letter does not mention competition policy, though the initial Mandate letter (December 2019) says, “You will also take steps to support consumer choice and competition to make life more affordable for middle class families.”

Policy action on other areas has aimed to address the unique competition issues raised by digital firms. For example, the government’s efforts to advance open banking would provide Canadians with more ownership of their banking data. It would also create more competition between Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft as well as smaller financial technology (fintech) companies as clients would be better able to transfer their accounts between financial institutions. Privacy legislation is being modernized in Canada to better protect citizen data, empower individuals and articulate appropriate commercial uses of digital information. On top of that, federal finance officials are exploring novel digital taxation models to capture some of the economic value generated by these firms.

The Department of Justice has also recently announced online consultations on modernizing Canada’s Privacy Act (#LetsTalkPrivacyAct) in acknowledgement that “Canadians’ expectations of privacy have changed and evolved since the Act became law more than three decades ago.” This rethinking of Canadian privacy law would enhance competition in the digital world by empowering Canadians to have more control over their personal information through the ability to request it from corporations and institutions. This in turn could act to reduce the assumed proprietary nature of user data as held by private entities. It is worth noting that Canada’s Privacy Commissioner has not hesitated to hold large tech firms accounting under federal private sector privacy law; filing a Notice of Application against Facebook (2020) and seeking clarity on whether Google’s search engine is subject to federal privacy law (2018).

It is worth mentioning that the Competition Bureau has taken cases that deal with dominance and data, particularly under the Competition Act’s abuse of dominance provisions. For example, in 2016 the Tribunal issued a favourable decision in the Competition Bureau’s suit against the Toronto Real Estate Board (TREB), an industry association of real estate brokers and sellers. The case hinged on rules that TREB imposed that limited access to real estate data, including the ability to display it online or to conduct in-depth analysis. The Tribunal found that these rules undermined the ability of innovative players in the space to offer new services in the Toronto area that would have made home sales and pricing data available online. As a result, consumers were denied access to better tools when shopping for homes.

While this case demonstrates the ability of the Competition Bureau to understand the impact of data on market power and competition, the decision does not speak directly to some of the key issues of digital dominance posed by the globe’s largest firms, as discussed in the previous section. A key difference between the TREB and digital giants like the FAANG companies is that TREB is an industry association made up of several businesses (brokers and other sellers), whereas FAANG companies are digital businesses. Organizations like TREB can gain dominance in the market by bringing agents together under one banner in a collaboration, whereas FAANG companies can create their dominant positions unilaterally. The ability of digital firms to achieve massive scale without having to depend on collaborations with other businesses is incredibly relevant for competition policy, because it blurs the distinction between competitive advantage and anti-competitive conduct.

V. Failures to Address the Problem

Despite efforts, Canada's competition policy system has been unable to effectively address the growing power of the most dominant digital firms to date and the potential abuses of their dominance. For example, after a three-year investigation, the Bureau called off its investigation into Apple and its potentially anticompetitive agreements with wireless carriers around the sale of iPhones. The Bureau was unable to find sufficient evidence that these agreements undermined competition.

Likewise, in 2016 the Bureau called off its investigation into Google and its potential abuse of its dominant position with respect to online search and advertising. After a three-year investigation, with over 130 interviews with “market participants'' (competitors, publishers, advertisers, wireless carriers, etc.) and with its collaboration with the US FTC and European Commission, the Bureau found that there was insufficient evidence to establish that Google intended to behave in an anticompetitive way and that its actions undermined competition.

However, during that investigation, Google committed to remove problematic clauses from its AdWords Application Programming Interface (API) Terms and Conditions anyway for a five-year period. This agreement mirrored a similar agreement struck by the US FTC resulting from its own investigation into Google. However, the resolution of both the Canadian and US investigation into Google contrasted strongly with the outcome of the European Commission’s investigation, which resulted in a €1.5B fine (1.29% of Google's turnover in 2018).

In contrast to competition authorities in the EU, Canadian merger enforcement in the tech sector has also been lacking. The most relevant example is the EU’s review of Google’s acquisition of Fitbit. While the Commission permitted the merger, it required Google, among other things, to implement a fire wall to separate its ad data from the health data collected through Fitbit. The Commission’s rationale for the requirement was that by “increasing the already vast amount of data that Google could use for the personalisation of ads, it would be more difficult for rivals to match Google's services.”

Our back-of-the-envelope analysis of the past six years of concluded merger reviews by the Competition Bureau suggests that less than 10% (8.9) of reviews concern Canada’s tech sector. In order to conduct this estimation, we considered how many of the concluded merger reviews had a North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code that was characterized as having “15% tech intensity” by the Brookfield Institute’s “the State of Canada's Tech Sector” report.

Alongside this infrequency, it is impossible to know whether and how the role and value of consumer data is considered in these merger reviews as it is not part of standard reporting.

Canadian merger enforcement in the tech sector has also been lacking. Our analysis of the past six years of concluded merger reviews by the Competition Bureau suggests that ~9% of reviews concern Canada’s tech sector. Out of these reviews, the Bureau did only three in-depth investigations, based on publicly available data.[6]

Another major oversight in Canadian enforcement in the digital space is the apparent lack of scrutiny of its own major digital firm: Shopify. Shopify, Canada’s largest public firm, provides digital architecture to facilitate e-commerce. Given its business, it has a strong and potentially dominant position across large swaths of the digital retail space. But does Shopify “win” in the same way that Amazon does – by “steamrolling rivals and partners”? We have not seen any evidence that the Bureau has been monitoring Shopify for similar behaviour that it is investigating with Amazon.

Shopify has also been acquiring other digital companies. Many of these transitions are “acquihires” intended to expand Shopify’s staff. But many of these transactions may also raise competition issues. Shopify’s recent acquisition of Handshake, an online wholesale platform, and 6 River Systems, which offers warehouse fulfillment solutions, signal its intent to move into the online wholesale space and vertically integrate. Shopify’s acquisition of Swedish startup Tictail, an online marketplace has enabled it to expand its consumer marketplace and potentially neutralize a competitor. Ultimately, we don’t know if these acquisitions have or will undermine competition because there is no evidence that the Bureau has looked into these deals or any other acquisition by Shopify. But what we do know is that through these acquisitions Shopify continues to grow, which may have serious implications for the competitiveness of the online retail (and now wholesale) space both in Canada and around the world.

One potential reason why the Bureau has taken relatively little action against digital firms is that competition policy in both Canada and elsewhere may not have the conceptual tools needed to identify competitive harm in the digital space. One reason why these authorities may lack the conceptual tools may be due to the exponential growth of digital commerce in the last decade. The FTC’s recent case against Facebook, which calls for Facebook to divest of WhatsApp and Instagram, illustrates this point. In 2014 and 2012, the FTC permitted Facebook to acquire WhatsApp and Instagram, respectively. The FTC’s current case could have been avoided if it understood the harm that those mergers would have caused. Even the European Commission overlooked the danger of Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp when it reviewed and subsequently permitted the merger.

In contrast, the Commission's 2020 review of Google’s acquisition of Fitbit gives us an example of how competition authorities can consider and mitigate the potential negative impact of data on competition. To get clearance from the Commission for the merger, Google was required to implement a firewall between its Google Ads data and the health data it collects from Fitbits and other wearables. This firewall prevents Google from linking the two data sources and using health data in its advertising algorithms, which the Commission asserts would “raise barriers to entry and expansion for Google's competitors for these services to the detriment of advertisers, who would ultimately face higher prices and have less choice”.

If the Competition Bureau were to review this merger (there is no evidence that it has) it is not certain (even unlikely) that it could negotiate the same terms in Canada given differences in EU and Canadian competition law. However, the Commission's foresight on the issue is an example of the type of analysis we will need more of from the Competition Bureau as the tech sector grows and data collection and utilization becomes a bigger part of everyday business. In the coming years, we will be able to assess the outcome of the Commission's decision and whether it went far enough to protect competition in the ads space.

Competition authorities in both Canada and abroad are struggling to understand competitive harm and dominance in the digital economy. But a lack of understanding about the unique ways that digital firms can undermine competition can only explain part of why the Competition Bureau has taken little enforcement action to-date. The Competition Bureau has in many instances been ineffective at protecting competition in key sectors, notably the media, grocery and telecom sector.

Canadian newspapers have been disrupted during the growth of social media platforms, in particular, Facebook. Alongside declining subscriptions and varying success with paywalls, newspapers have consolidated: by 2017, the four largest chains owned 68% of newspapers in Canada, with Postmedia Network Inc. owning nearly 45% of newspapers.

The Competition Bureau has done little to prevent this consolidation. In 2015 it issued a “No-Action Letter” for Postmedia’s acquisition of English-language newspapers from Quebecor Media Inc, which included The Toronto Sun, The Ottawa Sun, The Winnipeg Sun, The Calgary Sun and The Edmonton Sun, The London Free Press and the free 24 Hours newspapers in Toronto and Vancouver.[7] The Bureau claimed that Postmedia’s acquisitions would not “significantly lessen or prevent competition” because the acquired newspapers were not close rivals to the papers already owned by Postmedia, and free daily newspapers and social media provided competition in the marketplace.

The Bureau’s decision on Postmedia’s acquisitions is interesting because of its impact on free press in Canada. Because of this merger, many of Canada’s newspapers are now owned by one company, which gives Postmedia the potential to be an outsize influence over public discourse in Canada, and by extension, Canadian democracy. The Competition Act does not contain any language that allows the Bureau to block mergers that could undermine democracy or diversity of speech. In fact, the Act also does not give the Bureau the ability to block mergers that create dominant firms, strictly speaking. Section 92(2) of the Competition Act clearly states that the Bureau is unable to challenge mergers “solely on the basis of evidence of concentration or market share.” These two shortcomings of the Competition Act are significant weaknesses in the legislation that make us unable to mitigate the challenges that large tech firms may pose on our society and democracy until long after significant mergers have occurred.

There has also been increased concentration in the grocery space. In 2013, Sobeys Inc acquired over 200 groceries stores from Canada Safeway, as well as some liquor stores, distribution centres and food manufacturing faculties. To prevent challenge from the Competition Bureau, Sobeys was forced to divest of 23 stores. One year later, Loblaw Companies Limited acquired Shoppers Drug Mart Corporation. To sanctify the deal, Loblaw divested of stores in 27 markets. Regardless, the merger allowed Loblaw to nearly double its footprint and nearly triple the number of pharmacies it controls. The Competition Bureau reached a consent agreement in the Loblaw/Shoppers deal in 2014.

These grocery mergers carry implications for supply chain competition – i.e,. the sway that Loblaw and Sobeys in particular have over the supply side of the industry could be greater than the market share they hold through their stores. For three years, the Competition Bureau investigated whether Loblaw abused its power in the market to undermine competition. In 2017, the Bureau concluded its investigation. While there was evidence that Loblaw had bargaining power which could disadvantage suppliers, under the Competition Act, hard bargaining is not illegal (anticompetitive).

The Loblaw investigation highlights the distinction between bargaining and market power, as understood by the Competition Bureau, and has important implications for the application (or non-application) of competition law in cases of monopsony, particularly gig-work digital platforms. In Canada's 2008 submission to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Competition Committee titled Round table on monopsony and buyer power, the Bureau describes bargaining power as the power to reduce prices, but not to the point that sellers reduce their output. This contrasts with market power, which they understand as the ability to suppress prices so they are below the market’s “competitive level,” leading to a reduction in goods and services sold in the market. What this distinction means is that there is an incredibly high, if not impossible, standard that must be met for the Competition Bureau to identify and take action against monopsony power in markets, including labour markets governed by gig-work digital platforms. The power that these platforms wield must be so extreme that it forces workers out of work and potentially into poverty (if they are not already part of the working poor). We suggest that policy makers seriously rethink the standards used to identify abuses of dominance carried out by purchasers so that the law can be used to protect workers that work for digital platforms, or any other dominant employer for that matter.

Many Canadians are also acutely aware of oligopoly in the telecom sector and very high prices that Canadians pay for cell phone services. Oligopolist cell phone carriers in Canada are often referred to as the “big three” – Rogers, Bell and TELUS. As of 2017, these firms collectively made over 90% of all revenues for wireless services. While there is no hard evidence of collusion, Bell, TELUS and Rogers have an interesting history of matching price hikes. The Competition Bureau has also recognized that the “big three” coordinate their prices where there is not a strong regional competitor but likely do not have the tools to address this issue.

The Competition Bureau has undertaken minimal enforcement action in the sector. In 2013, the Bureau issued a No-Action Letter in response to TELUS’ acquisition of Public Mobile “due to the existence of effective remaining competition in each of the geographic areas where the parties’ wireless networks overlap.” This was despite the fact that based on the evidence collected Public Mobile was planning to discontinue its “Unlimited Talk” plan priced at $19/month.

In 2017, the Bureau permitted BCE Inc. (Bell) to purchase Manitoba Telecom Services (MTS), Manitoba’s provincial mobile carrier, subject to a consent agreement. Evidence from the investigation was clear: in regions where there is a regional competitor (SaskTel, tbaytel, Videotron and MTS), mobile prices are lower. The consent agreement for the deal required Bell to sell to TELUS “a significant number” of MTS wireless subscribers, as well as one-third of MTS’s retail locations. The agreement also required Bell to sell some of its spectrum to Xplornet, a provider of rural broadband internet services. The idea behind this divestment was that by selling this spectrum to Xplornet, the firm could then enter Manitoba’s mobile market and, in essence, take the place of MTS and thus maintain four competitors in the market. Research is needed to determine whether the Bureau’s plan to maintain a fourth competitor was effective.

While Canada’s competition agency has been ineffective at protecting competition in the telecom sector, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the government itself have stepped in to address the issue. The CRTC created the Wireless Code in 2013, which mandates that cell service providers cannot charge more than $100/month in international roaming charges, or $50 in data overage fees, unless the customer agrees to it. Reducing mobile prices is a priority of the current Liberal government, and former Minister Bains has instructed the country’s big three national wireless providers that they have two years to cut their basic prices for cell phone services by 25%, pledging to step in to cut prices if they do not comply. This will prove a major test of political will and policy power to stop the Canadian cell phone oligopoly.

Indeed, weak competition policy has surely contributed to the ongoing entrenchment of oligopolies in Canada which have “thrived” despite the pandemic: the airline duopoly of WestJet and Air Canada control more than 80% of the airline industry, the banking industry is largely controlled by the “big five,” and when it comes to the wireless industry, the three biggest companies (Rogers, Bell and Telus) capture nearly 89% of the telecommunications market.

VI. Comparing Canada’s competition policy to the US and EU

There are many reasons why Canada’s current competition policy framework may not be up to the task of addressing competitive problems in the intangible economy (let alone the tangible one), such as: insufficient and declining funding, seemingly arbitrary notification thresholds for merger reviews, the inability to conduct market studies to track trends in the sector, a comparatively weak mandate and a lack of a recent review.

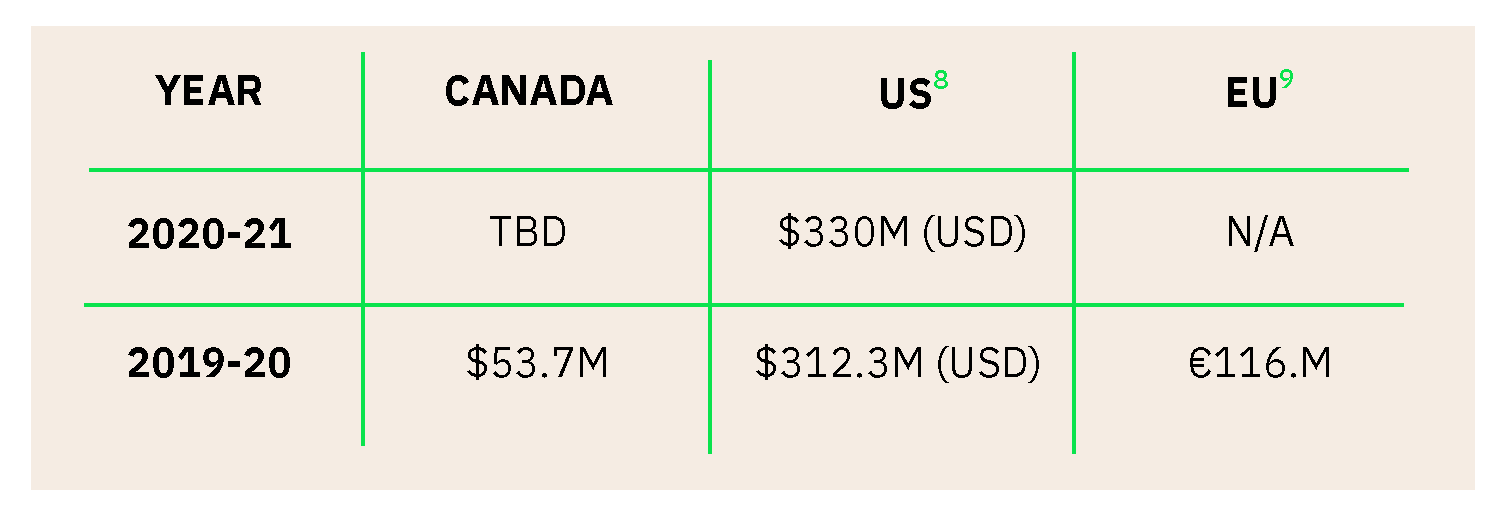

Insufficient funding to the Competition Bureau has been cited as an issue and is paltry when compared to peers in the US or the EU. It is also worth noting that in the US, the FTC also has state-based competition authorities and the DOJ, which further enhance the US’ capacity to investigate firms.

Funding for Canada’s Bureau has also modestly decreased over time (Table 3).

A related issue is the now somewhat arbitrary notification thresholds for mergers. Currently, businesses must notify the Bureau if they are engaging in a merger worth $96M and the parties combined have $400M in assets or revenues in Canada. However, some transactions, particularly those involving tech startups, may fall far under that threshold and may never come to the attention of the Bureau. But, even if the Bureau committed to reviewing more mergers, it may not have sufficient resources to do so. This under-resourcing could lead to uneven, insufficient enforcement, which is a failure of competition policy.

When it comes to contemporary issues at the intersection of media, technology and democracy, Canadian competition policy is ill-suited to thoughtfully evaluate digital mergers. The legislation simply lacks the foresight to make a meaningful difference. As companies have evolved to leverage the acquisition of data and associated consumer insights, problematic mergers may have been missed.

Another major barrier to enforcing the law in the digital space is that the Competition Act does not allow the Bureau to undertake market studies. In other jurisdictions, like those in the US, competition authorities can study specific markets by compelling information from businesses. This enforcement tool is very powerful because it allows agencies to identify problems that may not be revealed through publicly available information. For example, the FTC issued special orders to the “big five” tech companies – Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft – as part of a study into acquisitions they made from 2010 to 2020. It may not be a coincidence that less than a year later the FTC brought a case against Facebook regarding its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp.

Currently, the Bureau can only compel businesses to disclose information during the course of an investigation, and the information they are entitled to is limited to the scope of the investigation. To enhance the Bureau’s ability to enforce the Competition Act in the digital sphere, it should be given the same power to do in-depth market studies with businesses’ own information. Canada’s Competition Bureau needs more of a toolkit. If Canadian authorities could conduct a market study, businesses would be compelled to co-operate and provide information that illuminate market trends that are potentially anti-competitive.

It’s also worth noting that competition policy is not the only realm of the policy sphere that has struggled to keep pace with the growth of the intangibles economy. Provincial Consumer Protection authorities did not conceive of a relationship between users of a service that engaged in an exchange “for free.” So far, it seems that Google Play and the App Store have emerged as possibly the most effective regulators of digital firms.

To address the unique competition issues arising from the digital economy, we need to reconceptualize what competitive harm means in the digital sphere. But conceiving of a new way of understanding the unique competitive harms of the digital economy is not enough. We also need a broader philosophy and motivation behind our national competition policy that is compatible with this new understanding of competitive harm. This is something Canada currently lacks, but could reshape if it were to re-examine its competition legislation.

Competition policies around the globe are guided by a purpose; competition is a means of creating some sort of economic or social outcome. In Canada, the purpose statement of the Competition Act states that the aim of the Act is to 1) promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy, 2) expand opportunities for Canadian participation in world markets while at the same time recognizing the role of foreign competition in Canada, 3) ensure that small and medium-sized enterprises have an equitable opportunity to participate in the Canadian economy and 4) provide consumers with competitive prices and product choices.

But historically, despite the purpose statement of the Act, competition thinkers in Canada have prioritized efficiency over all other considerations including consumer prices. This thinking shows up in key parts of the Act, such as the “efficiencies defense” for mergers. Under section 96.1 of the Act, mergers that will increase prices are legal if they create efficiencies that are “greater than and offset” the “competitive harm” of the merger.[10]

Since, to many, the sole aim of competition policy in Canada is to enhance efficiency in the economy, conceptions of competitive harm are also focused on efficiency. That is, when businesses undermine competition, it is only bad when this hurts the efficiency of their business or the market, not because it hurts consumers, users of digital services or even democracy. Even if policy thinkers were to create new conceptions of competitive harm for the digital era, we would likely not be able to use them because they are incompatible with the current philosophy that underpins our competition policy system. This means that the conceptions would be incompatible with our law, but also the views of key decision makers within Canada’s competition policy system. For example, the efficiency defence could override a modernized interpretation of consumer harm.

The rationale put forward in the Interim Report raises questions about competition policy in both the intangible and tangible economy. First, the assumption that competition has nothing to do with diffusing economic power may be incorrect, as our experiences with social media platforms in this century highlight how these social media platforms erode privacy, spread misinformation and hate speech, accelerate political polarization and threaten the integrity of elections.

Further, thinkers in the previous century could not have conceived of the digital economy we live in today. Not only are many markets different (e.g., zero cost) but notions of efficiency seem outdated in a world with zero or close-to-zero marginal cost and the most valuable capital being intellectual property and human capital. The widget plants of the 1970s simply cannot be compared to the digital firms of today, which are able to quickly achieve unprecedented scale due to the borderless nature of the digital economy.

Similarly, the single-minded obsession with efficiency overlooks and outright dismisses the important social implications of power and concentration on the digital economy and surveillance capitalism. In our new economic reality, the magnitude of digital firms and the way they wield data can influence us in multiple and clandestine ways. Competition policy has an important role to play in mitigating this power, but it cannot do that if the law is not set up to do so and if the people that enforce it believe that mitigating economic power is not their job.

In fact, some prominent competition thinkers in Canada have been outright hostile to the idea that competition policy should be concerned with the social implications of the digital economy, or the social implications of competition in general. A term used by critics to describe views about competition policy that deviate from the status-quo, efficiencies-centric view is “hipster antitrust”. Coined in the US, so-called “antitrust hipsters” want to see American competition policy abandon the current obsession with efficiency and instead prioritize the original purpose of antitrust laws, namely to curb the power of giant firms and protect against their economic exploitation.

In Canada, some people have been using the term to discredit and undermine critics of the efficiency-centric status-quo. The supposed “hipster-antitrust-isim” has been vilified in Canada as an import from the US that is misinformed, hysteric and threatens to undermine the competitiveness of the Canadian economy. But in truth, it is the efficiency-centric view of competition policy that was imported from the US and threatens to undermine the welfare of our economy and society.

In Canada, there is little research on the state of competition and competitiveness. But evidence from the US, which was also captured by the Chicago School ideology for decades, illustrates that laxer laws, as advanced by Chicago School adherents, have (not surprisingly) undermined competition and innovation. With the Washington Centre of Equitable Growth, Professor Fiona M. Scott Morton of the Yale University School of Management has compiled a database of over 100 academic papers published since 2000 that highlight the impact of more lax enforcement of competition law.

In one of these papers, Bruce A. Blonigen and Justin R. Pierce demonstrate that most M&A activity in US manufacturing sectors from 1997 to 2007 is associated with higher prices but not greater productivity or efficiency. In another paper presented in the database by Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer and Song Ma, the authors show that “killer acquisitions” are a real phenomenon that undermine innovation in the pharmaceutical sector. Furthermore, many of these mergers do not meet notification thresholds, meaning that they are likely not reviewed by competition authorities. In a 2019 paper, Justus Haucap, Alexander Rasch and Joel Stiebale study the impact of mergers on innovation in the pharmaceutical sector and find that, contrary to the theories put forward by Chicago School adherents, innovation (measured as patents) declines substantially after a merger.

Outside of the database completed by Morton, there has also been recent research on the interplay between the stringency of competition law and innovation. A 2020 paper by Ross Levine and others undertook an analysis of 66 countries from 1991 to 2015 and found that competition laws that are more stringent are associated with an increased number of patents, among other measures.

VII. Areas of Opportunity

While by no means exhaustive, we offer the following list as a starting point to catalyze further thinking regarding the modernization of competition policy in Canada:

It is time for the Competition Bureau to consider the value and power of consumer data and the associated advantages it can create. This was essentially one of the recommendations in the 2018 Canadian House of Commons report “Democracy Under Threat: Risks and Solutions in the Era of Disinformation and Data Monopoly”: to “study the potential economic harms caused by data-opolies and determine whether the Competition Act should be modernized.”

Consider the benefits of giving the Bureau the power to do market studies like competition authorities in the US.

Revise the Competition Act to remove the ability for the Competition Bureau to issue “Advance Ruling Certificates” for mergers, which commits the Bureau will never revisit a merger after it is reviewed.

The Bureau should review digital mergers that have taken place over the past decade and flag harmful mergers that it may have overlooked due to an outdated conception of consumer harm and high merger notification thresholds.

Consider taking the Competition Bureau out of the Ministry of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development in order to reduce the perception of political interference.

Consider dropping the efficiencies defence. A past commissioner of the Competition Bureau has called for dropping the efficiencies defense from the Competition Act.

Create an independent Canadian Competitiveness Council that would report to Parliament and take on the advocacy and policy work for competition.[11]

Mandate more diversity on the Competition Tribunal. The Employment Insurance (EI) system, with its tri-partied oversight structure, could serve as a model.

Commit to reviewing the Competition Act every five years, like the Banking Act. This will keep the legislation up-to-date.

As described, competition authorities should modernize Canada’s legislative definition of consumer harm for a digital age.

Consider the potential of a "balance of harm test" as suggested at the Competition Bureau’s 2019 Data Forum, given the particular challenges of acquisitions in the tech space. Such a test could be more economically accurate as it could consider both the scale and the likelihood of harm in merger cases involving potential prevention of future competition.

Ultimately, there are inherent limitations to Canada’s potential recalibration of Competition Policy for a digital age. Many of these “wicked” problems catalyzed by the largest technology firms are international, meaning that national policy instruments may be insufficient to moderate global trends, especially where substantial variance among competition approaches persists.

Conclusion

It is difficult to say why Canada’s competition policy has failed to substantively evolve in a rapidly digitizing age, and encouraging to know that a review of the Act is somewhere on the federal government’s agenda. That said, over the past few years, a series of compelling recommendations to improve competition policy in Canada have been made at various times. Given the richness of these proposals, it seems to us that the country has lacked the political will to prioritize comprehensive competition reform in a digital era and is now playing catch up. It is imperative that recent antitrust actions in the US and the EU catalyze more rigorous review of the limitations of and opportunities for competition policy in Canada.

Research undertaken in this century has begun to cast doubt on the theories that have informed our current competition policy and continue to inform it. Therefore, we need to revitalize our national competition policy in two key ways. First, we need to examine the underlying premise that the primary aim of competition policy is to promote economic efficiency, and replace it with a more balanced view that considers the many ways that competition makes our economy, society and democracy better. From this foundation, we can develop new ways of understanding competitive harm that are relevant to our digital era. In particular, we can develop understandings and methods for assessing the competitive harm that arises from data extraction and surveillance capitalism.

Our traditional theories and understandings of competition policy are becoming irrelevant as our economy becomes increasingly dominated by large digital firms. To move forward, we need to fundamentally shift away from price-based competition considerations that do not capture the role and value of consumer data in driving firm valuation.

It will be critical for Canada’s competition authority to redefine “dominance” via volume of data and also understand the competitive harms that can flow from dominant firms that hold large volumes of data. We must reconsider the role of data as an “asset” inthe intangible economy as we recalibrate competition policy for a digital age. Many current aspects of competition policy are worth revisiting and this rich, big data and insight-driven environment further invites more sophisticated scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions.

As competition-policy “outsiders” begin to discuss these issues and lay critiques of the current system, we should expect to see others lash out and attempt to discredit. We have already seen some small incidences of this behaviour in the Canadian discussion.

At the same time, it is critical to note that there are vested interests in the conversation that aim to influence core thinking on competition policy. For instance, the Global Antitrust Institute is funded by Google, Amazon and Qualcomm and sponsors conferences and dinners for competition law enforcement to advance theories of competition law that may suit their interests. The Institute Includes officials from the US as well as Australia, Brazil, China and Japan.[12] In contrast, in Canada, much of the policy conversation is hosted by the Canadian Bar. The Bar hosts a bi-annual conference that brings together lawyers representing corporations, economic experts and Bureau officers and management. It also publishes a journal that lawyers, consultants, academics and officers publish in. The Canadian Economic Association also provides a platform for conversation on technical aspects of competition policy. It seems like Canadian competition policy may be more insulated from corporate influence. While corporate interests should be fairly included in conversations on competition policy, they should not be left to host and guide meaningful discussions that are intended to share policy.

As policy makers who are not competition policy insiders navigate the issues of competition in the digital economy, it will be important to not only engage with diverse views on the subject, but also be aware of vested interests and rhetorical strategies used to undermine certain perspectives.

These policy changes won’t happen in a vacuum. The government’s efforts to advance open banking provides a novel opportunity to contextualize our proposed rethink of Canada’s competition policy by evening the playing field for fintech companies and the “big five” banks.

As a policy community we have the opportunity to deeply consider what it would look like for Canada’s competition policy to truly “be at the forefront of the digital economy.” We need to rigorously reimagine the role of competition policy, with less emphasis on efficiency and more emphasis on pressing economic issues of our time such as the role of customer data in a merger and acquisition, modern notions of consumer harm, implications for trade and the impacts on wages and the labour market.

But this necessity is not universally acknowledged. Some may argue that these approaches are not valid or appropriate under the umbrella of competition policy. There are many actors in Canada’s competition policy space that believe that Canada should not take more action on digital firms; and there are also dissenting opinions that make a strong case for strategic reform.

It is imperative that recent antitrust actions in the US and the EU guide Canada to engage in a more rigorous review of the limitations of and opportunities for competition policy. If we don’t take action, we risk creating a world where our lives are dominated by corporate giants; undermining our democratic institutions and the media. Without action, we risk allowing our democracy to devolve into a corporate-rune plutocracy. The social and economic issues of digital dominance are massive and cannot be ignored any longer. A rigorous review of the Competition Act is a worthwhile – if not overdue – exercise for Canadians.

Appendix A: Glossary

Acquisition: The Competition Act defines a merger as the acquisition or establishment – whether by purchase or lease of shares or assets, or by amalgamation, combination or otherwise – of control over or a significant interest in all or part of a business.

Anti-competitive behaviour: Anti-competitive practices are business or government practices that unlawfully prevent or reduce competition in a market.

Antitrust: Antitrust laws are regulations that encourage competition by limiting the market power of any particular firm. This often involves ensuring that mergers and acquisitions don't overly concentrate market power or form monopolies, as well as breaking up firms that have become monopolies.

Advance Ruling Certificate (ARC): An Advance Ruling Certificate (ARC) may be issued by the Commissioner to a party or parties to a proposed merger transaction who want to be assured that the transaction will not give rise to proceedings under section 92 of the Act.

Chicago School of economics: The Chicago School is a neoclassical economic school of thought that originated at the University of Chicago in the 1930s. The main tenets of the Chicago School are that free markets best allocate resources in an economy and that minimal, or even no, government intervention is best for economic prosperity.

Collusion: Collusion is a deceitful agreement or secret cooperation between two or more parties to limit open competition by deceiving, misleading or defrauding others of their legal right. Collusion is not always considered illegal.

Competition policy: Government policy that seeks to promote competition and efficiency in different markets and industries.

Efficiency Defence: Canada has a defence (Section 96 (1) of the Competition Act) that allows efficiency enhancing mergers and collaborations between competitors.

“Kill Zone”: Used to refer to the practice of large technology firms purchasing rivals in an attempt to minimize (“kill”) competition.

Market study: Market studies allow the Bureau to examine an industry or business sector from a competition perspective in order to identify relevant laws, policies, regulations or other factors that may impede competition. In some jurisdictions (not including Canada), competition authorities can compel internal information from businesses to study trends in the market and identify potentially anti-competitive behaviour.

Merger: Section 91 of the Competition Act defines a "merger" as "…the acquisition or establishment, direct or indirect, by one or more persons, whether by purchase or lease of shares or assets, by amalgamation or by combination or otherwise, of control over or significant interest in the whole or a part of a business of a competitor, supplier, buyer or other person."

Monopoly: a market structure where a firm is the sole provider of a good or service. There is no definition of “monopoly” in Canada’s Competition Act. A previous definition was repealed in 1985.

Market (monopoly) power: where a firm or group of firms have the ability to raise prices over the competitive level (and decrease output), decrease the quality of their good/service or otherwise exert control over a market and consumers in it.

Monopsony: a market structure where a firm is the sole purchaser of a good or service. The price of an input is depressed below the competitive level such that it results in a decrease in the overall quantity of the input produced or supplied in a relevant market.

Monopsony power: refers to when a firm or group of firms has the ability to reduce or suppress prices charged by suppliers (i.e. business, workers) or otherwise exert control over a market and the sellers in it.

No-action letter (NAL): A no-action letter (NAL) may be issued by the Commissioner of Competition to indicate that he or she does not intend to challenge a proposed merger under the Competition Act.

Vertical integration: The combination in one company of two or more stages of production normally operated by separate companies.

Appendix B: Table 4 – Competition Enforcement Action Canada, the US, the UK and EU: 1994 to Today

* These cases pertain to misrepresentation and misleading advertising, which are not competition concerns, strictly speaking.

Endnotes[1] Monopolized: Life in the Age of Corporate Power

[2] This update addressed: deceptive marketing, restitution, abuse of dominance, pricing provisions, price maintenance, competitor collaboration, merger review, bid-rigging and obstruction and non-compliance.

[3] The article highlights five key challenges posed by the digital monopolies: risk of data breaches, data control, attention as currency, lack of transparency and political influence.

[4] Zuboff defines surveillance capitalism as “the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. These data are then computed and packaged as prediction products and sold into behavioral futures markets — business customers with a commercial interest in knowing what we will do now, soon, and later.”